Background: Bahrain’s small size and central location among Persian Gulf countries require it to play a delicate balancing act in foreign affairs among its larger neighbors. Possessing minimal oil reserves, Bahrain has turned to petroleum processing and refining, and has transformed itself into an international banking center. The new amir is pushing economic and political reforms, and has worked to improve relations with the Shi’a community. In 2001, the International Court of Justice awarded the Hawar Islands, long disputed with Qatar, to Bahrain.

Government type: traditional monarchy

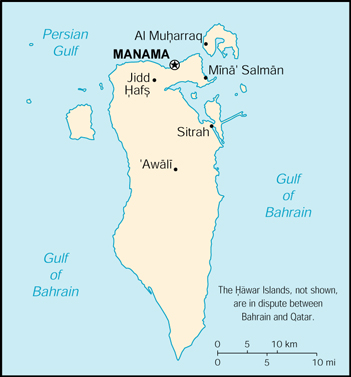

Capital: Manama

Currency: 1 Bahraini dinar (BD) = 1,000 fils

Geography of Bahrain

Location: Middle East, archipelago in the Persian Gulf, east of Saudi Arabia

Geographic coordinates: 26 00 N, 50 33 E

Area:

total: 620 sq. km

land: 620 sq. km

water: 0 sq. km

Land boundaries: 0 km

Coastline: 161 km

Maritime claims:

contiguous zone: 24 nm

continental shelf: extending to boundaries to be determined

territorial sea: 12 nm

Climate: arid; mild, pleasant winters; very hot, humid summers

Terrain: mostly low desert plain rising gently to low central escarpment

Elevation extremes:

lowest point: Persian Gulf 0 m

highest point: Jabal ad Dukhan 122 m

Natural resources: oil, associated and non-associated natural gas, fish

Land use:

arable land: 1%

permanent crops: 1%

permanent pastures: 6%

forests and woodland: 0%

other: 92% (1993 est.)

Irrigated land: 10 sq km (1993 est.)

Natural hazards: periodic droughts; dust storms

Environment – current issues: desertification resulting from the degradation of limited arable land, periods of drought, and dust storms; coastal degradation (damage to coastlines, coral reefs, and sea vegetation) resulting from oil spills and other discharges from large tankers, oil refineries, and distribution stations; no natural fresh water resources so that groundwater and sea water are the only sources for all water needs.

Environment – international agreements:

party to: Biodiversity, Climate Change, Desertification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Ozone Layer Protection, Wetlands

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

Geography – note: close to primary Middle Eastern petroleum sources; strategic location in Persian Gulf which much of Western world’s petroleum must transit to reach open ocean.

Bahrain (from the Arabic word for “two seas”) comprises an archipelago of thirty-three islands situated midway in the Persian Gulf close to the shore of the Arabian Peninsula. The islands are about twenty-four kilometers from the east coast of Saudi Arabia and twenty-eight kilometers from Qatar. The total area of the islands is about 691 square kilometers, or about four times the size of the District of Columbia. The largest island, accounting for 83 percent of the area, is Bahrain (also seen as Al Bahrayn), which has an extent of 572 square kilometers. From north to south, Bahrain is forty-eight kilometers long; at its widest point in the north, it is sixteen kilometers from east to west.

Around most of Bahrain is a relatively shallow inlet of the Persian Gulf known as the Gulf of Bahrain. The seabed adjacent to Bahrain is rocky and, mainly off the northern part of the island, covered by extensive coral reefs. Most of the island is low-lying and barren desert. Outcroppings of limestone form low rolling hills, stubby cliffs, and shallow ravines. The limestone is covered by various densities of saline sand, capable of supporting only the hardiest desert vegetation–chiefly thorn trees and scrub. There is a fertile strip five kilometers wide along the northern coast on which date, almond, fig, and pomegranate trees grow. The interior contains an escarpment that rises to 134 meters, the highest point on the island, to form Jabal ad Dukhan (Mountain of Smoke), named for the mists that often wreathe the summit. Most of the country’s oil wells are situated in the vicinity of Jabal ad Dukhan.

Manama (Al Manamah), the capital, is located on the northeastern tip of the island of Bahrain. The main port, Mina Salman, also is located on the island, as are the major petroleum refining facilities and commercial centers. Causeways and bridges connect Bahrain to adjacent islands and the mainland of Saudi Arabia. The oldest causeway, originally constructed in 1929, links Bahrain to Al Muharraq, the second largest island. Although the island is only six kilometers long, the country’s second largest city, Al Muharraq, and the international airport are located there. A causeway also connects Al Muharraq to the tiny island of Jazirat al Azl, the site of a major ship-repair and dry-dock center. South of Jazirat al Azl, the island of Sitrah, site of the oil export terminal, is linked to Bahrain by a bridge that spans the narrow channel separating the two islands. The causeway to the island of Umm an Nasan, off the west coast of Bahrain, continues on to the Saudi mainland town of Al Khubar. Umm an Nasan is the private property of the amir and the site of his personal game preserve.

The other islands of significance include Nabi Salah, which is northwest of Sitrah; Jiddah, to the north of Umm an Nasan; and a group of islands, the largest of which is Hawar, near the coast of Qatar. Nabi Salah contains several freshwater springs that are used to irrigate the island’s extensive date palm groves. The rocky islet of Jiddah houses the state prison. Hawar and the fifteen small islands near it are the subject of a territorial dispute between Bahrain and Qatar. Hawar is nineteen kilometers long and about oneand onehalf kilometers wide. The other islands are uninhabited and are nesting sites for a variety of migratory birds.

Climate

Bahrain has two seasons: an extremely hot summer and a relatively mild winter. During the summer months, from April to October, afternoon temperatures average 40° C and can reach 48° C during June and July. The combination of intense heat and high humidity makes this season uncomfortable. In addition, a hot, dry southwest wind, known locally as the qaws, periodically blows sand clouds across the barren southern end of Bahrain toward Manama in the summer. Temperatures moderate in the winter months, from November to March, when the range is between 10° C and 20° C. However, humidity often rises above 90 percent in the winter. From December to March, prevailing winds from the southeast, known as the shammal, bring damp air over the islands. Regardless of the season, daily temperatures are fairly uniform throughout the archipelago.

Bahrain receives little precipitation. The average annual rainfall is seventy-two millimeters, usually confined to the winter months. No permanent rivers or streams exist on any of the islands. The winter rains tend to fall in brief, torrential bursts, flooding the shallow wadis that are dry the rest of the year and impeding transportation. Little of the rainwater is saved for irrigation or drinking. However, there are numerous natural springs in the northern part of Bahrain and on adjacent islands. Underground freshwater deposits also extend beneath the Gulf of Bahrain to the Saudi Arabian coast. Since ancient times, these springs have attracted settlers to the archipelago. Despite increasing salinization, the springs remain an important source of drinking water for Bahrain. Since the early 1980s, however, desalination plants, which render seawater suitable for domestic and industrial use, have provided about 60 percent of daily water consumption needs.

People of Bahrain

Most of the population of Bahrain is concentrated in the two principal cities, Manama and Al Muharraq. The indigenous people–66% of the population–are from the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. The most numerous minorities are Europeans and South and East Asians.

Islam is the official religion. Though Shi’a Muslims make up more than two-thirds of the population, Sunni Islam is the prevailing belief held by those in the government, military, and corporate sectors. Roman Catholic and Protestant churches, as well as a tiny indigenous Jewish community, also exist in Bahrain.

Bahrain has traditionally boasted an advanced educational system. Schooling and related costs are entirely paid for by the government, and, although not compulsory, primary and secondary attendance rates are high. Bahrain also encourages institutions of higher learning, drawing on expatriate talent and the increasing pool of Bahrainis returning from abroad with advanced degrees. Bahrain University has been established for standard undergraduate and graduate study, and the College of Health Sciences–operating under the direction of the Ministry of Health–trains physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and paramedics.

Population: 688,345 (July 2005 est.)

note: includes 235,108 non-nationals

Age structure:

0-14 years: 29.6%

15-64 years: 67.43%

65 years and over: 2.97%

Population growth rate: 1.73%

Birth rate: 20.07 births/1,000 population

Death rate: 3.92 deaths/1,000 population

Net migration rate: 1.1 migrant(s)/1,000 population

Infant mortality rate: 19.77 deaths/1,000 live births

Life expectancy at birth:

total population: 73.2 years

male: 70.81 years

female: 75.67 years

Total fertility rate: 2.79 children born/woman

Nationality:

noun: Bahraini(s)

adjective: Bahraini

Ethnic groups: Bahraini 63%, Asian 19%, other Arab 10%, Iranian 8%

Religions: Shi’a Muslim 70%, Sunni Muslim 30%

Languages: Arabic, English, Farsi, Urdu

Literacy:

definition: age 15 and over can read and write

total population: 85.2%

male: 89.1%

female: 79.4% (1995 est.)

History of Bahrain

Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates have assumed added prominence as a result of Operation Desert Shield in 1990 and the Persian Gulf War in 1991. These states share certain characteristics while simultaneously differing from one another in various respects. Islam has played a major role in each of the Persian Gulf states, although Kuwait and Bahrain reflect a greater secular influence than the other three. Moreover, the puritanical Wahhabi Sunni sect prevails in Qatar; Bahrain has a majority population of Shia, a denomination of the faith that constitutes a minority in Islam as a whole; and the people of Oman represent primarily a minor sect within Shia Islam, the Ibadi.

The beduin heritage also exerts a significant influence in all of the Persian Gulf states. In the latter half of the twentieth century, however, a sense of national identity increasingly has superseded tribal allegiance. The ruling families in the Persian Gulf states represent shaykhs of tribes that originally settled particular areas; however, governmental institutions steadily have taken over spheres that previously fell under the purview of tribal councils.

Historically, Britain exercised a protectorate at least briefly over each of the Persian Gulf states. This connection has resulted in the presence of governmental institutions established by the United Kingdom as well as strong commercial and military ties with it. Sources of military matériel and training in the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, were being provided by other countries in addition to the United Kingdom.

Because of the extensive coastlines of the Persian Gulf states, trade, fishing, shipbuilding, and, in the past, pearling have represented substantial sources of income. In the early 1990s, trade and, to a lesser extent, fishing, continued to contribute major amounts to the gross domestic product of these states.

Of the five states, Oman has the least coastal area on the Persian Gulf because its access to that waterway occurs only at the western tip of the Musandam Peninsula, separated from the remainder of Oman by the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Partly as a result of this limited contact with the gulf and partly because of the mountains that cut off the interior from the coast, Oman has the most distinctive culture of the five states.

In general, the gulf has served as a major facilitator of trade and culture. The ancient civilization of Dilmun, for example, in present-day Bahrain existed as early as the fourth millennium B.C.

The Persian Gulf, however, also constitutes a ready channel for foreign conquerors. In addition to Britain, over the centuries the gulf states have known such rulers as the Greeks, Parthians, Sassanians, Iranians, and Portuguese. When England’s influence first came to the area in 1622, the Safavid shah of Iran sought England’s aid in driving the Portuguese out of the gulf.

Britain did not play a major role, however, until the early nineteenth century. At that time, attacks on British shipping by the Al Qasimi of the present-day UAE became so serious that Britain asked the assistance of the ruler of Oman in ending the attacks. In consequence, Britain in 1820 initiated treaties or truces with the various rulers of the area, giving rise to the term Trucial Coast.

The boundaries of the Persian Gulf states were considered relatively unimportant until the discovery of oil in Bahrain in 1932 caused other gulf countries to define their geographic limits. Britain’s 1968 announcement that in 1971 it would abandon its protectorate commitments east of the Suez Canal accelerated the independence of the states. Oman had maintained its independence in principle since 1650. Kuwait, with the most advanced institutions–primarily because of its oil wealth–had declared its independence in 1961. Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE followed suit in 1971. In the face of the Iranian Revolution of 1979, all of the Persian Gulf states experienced fears for their security. These apprehensions led to their formation, together with Saudi Arabia, of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in May 1981.

Bahrain, the only island state of the five Persian Gulf states, came under the rule of the Al Khalifa (originally members of the Bani Utub, an Arabian tribe) in 1783 after 180 years of Iranian control. Prior to 1971, Iran intermittently reasserted its claim to Bahrain, two-thirds of whose inhabitants are Shia Muslims although the ruling family is Sunni Muslim. Because of sectarian tensions, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and its aftermath had an unsettling effect on the population; the government believed that a number of Shia plots during the 1980s received clandestine support from Iran. In 1992 the island’s predominantly urban population (85 percent) consisted of 34 percent foreigners, who accounted for 55 percent of the labor force. The exploitation of oil and natural gas–Bahrain was the first of the five Persian Gulf states in which oil was discovered–is the island’s main industry, together with the processing of aluminum, provision of drydock facilities for ships, and operation of offshore banking units.

The Al Khalifa control the government of Bahrain and held eight of eighteen ministerial posts in early 1994. A brief experiment in limited democracy occurred with the December 1972 elections for a Constituent Assembly. The resulting constitution that took effect in December 1973 provided for an advisory legislative body, the National Assembly, voted for by male citizens. The ruler dissolved the assembly in August 1975. The new Consultative Council, which began debating labor matters in January 1993, is believed to have had an impact on the provisions of the new Labor Law enacted in September 1993.

Bahrain’s historical concern over the threat from Iran as well as its domestic unrest prompted it to join the GCC at the organization’s founding in 1981. Even within the GCC, however, from time to time Bahrain has had tense relations with Qatar over their mutual claim to the island of Hawar and the adjacent islands located between the two countries; this dispute was under review by the International Court of Justice at The Hague in early 1994. Bahrain traditionally has had good relations with the West, particularly the United Kingdom and the United States. Bahrain’s cordial association with the United States is reflected in its serving as homeport for the commander, Middle East Force, since 1949 and as the site of a United States naval support unit since 1972. In October 1991, following participation in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, Bahrain signed a defense cooperation agreement with the United States.

Bahrain’s relationship with Qatar is long-standing. After the Al Khalifa conquered Bahrain in 1783 from their base in Qatar, Bahrain became the Al Khalifa seat. Subsequently, tribal elements remaining in Qatar sought to assert their autonomy from the Al Khalifa. Thus, in the early nineteenth century, Qatar was the scene of several conflicts involving the Al Khalifa and their rivals, the Al Thani, as well as various outsiders, including Iranians, Omanis, Wahhabis, and Ottomans. When the British East India Company in 1820 signed the General Treaty of Peace with the shaykhs of the area designed to end piracy, the treaty considered Qatar a dependency of Bahrain. Not until the signing of a treaty with Britain by Abd Allah ibn Qasim Al Thani in 1916 did Qatar enter into the Trucial States system as an “independent” protectorate. Britain’s 1971 withdrawal from the Persian Gulf led to Qatar’s full independence in that year.

The gulf countries recognize the potential threats they face, particularly from Iraq and possibly from Iran. In addition, they have experienced the need to counter domestic insurgencies, protect their ruling families and oil installations, and possibly use military force in pursuing claims to disputed territory. A partial solution to their defense needs lay in the formation of the GCC in 1981.

The Persian Gulf War brought with it the realization that the GCC was inadequate to provide the gulf states with the defense they required. As a result, most of the states sought defense agreements with the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia, more or less in that order. Concurrently, the gulf countries have endeavored to improve the caliber and training of their armed forces and the interoperability of military equipment through joint military exercises both within the GCC framework and with Western powers. The United States has sought to complement GCC collective security efforts and has stated that it does not intend to station forces permanently in the region.

At a November 1993 meeting, GCC defense ministers made plans to expand the Saudi-based Peninsula Shield forces, a rapid deployment force, to 25,000. The force is to have units from each GCC state, a unified command, and a rotating chairmanship. The ministers also agreed to spend up to US$5 billion to purchase three or four more AWACS aircraft to supplement the five the Saudi air force already has and to create a headquarters in Saudi Arabia for GCC defense purposes. The UAE reportedly considered the proposed force increase insufficient; furthermore, Oman sought a force of 100,000 members.

In addition to these efforts, directed at the military aspects of national security, declining oil revenues for many of the states and internal sectarian divisions also have led the gulf countries to institute domestic efforts to strengthen their national security. Such efforts entail measures to increase the role of citizens in an advisory governmental capacity, to allow greater freedom of the press, to promote economic development through diversification and incentives for foreign investment, and to develop infrastructure projects that will increase the standard of living for more sectors of the population, thereby eliminating sources of discord. The ruling families hope that such steps will promote stability, counter the possible appeal of radical Islam, and ultimately strengthen the position of the ruling families in some form of limited constitutional monarchy.

Bahrain Economy

Bahrain has a mixed economy, with government control of many basic industries, including the important oil and aluminum industries. Between 1981 and 1993, Bahrain Government expenditures increased by 64%. During that same time, government revenues continued to be largely dependent on the oil industry and increased by only 4%. Bahrain has received significant budgetary support and project grants from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.

Privatization could help Bahrain’s economy. However, as of the Spring 2001 the government of Bahrain still wholly owned the Bahrain Petroleum Company. Utilities, banks, financial services, and telecommunications have started though, to come under the control of the private sector.

The government has used its modest oil revenues to build an advanced infrastructure in transportation and telecommunications. Bahrain is a regional financial and business center. Regional tourism also is a significant source of income. Bahrain benefited from the region’s economic boom in the late 1970s and 1980s. During that time, the government emphasized infrastructure development and other projects to improve the standard of living; health, education, housing, electricity, water, and roads all received attention.

Petroleum and natural gas, the only significant natural resources in Bahrain, dominate the economy and provide about 60% of budget revenues. Bahrain was the first Arabian Gulf state to discover oil. Because of limited reserves, Bahrain has worked to diversify its economy over the past decade. Bahrain has stabilized its oil production at about 40,000 barrels per day (b/d), and reserves are expected to last 10-15 years. The Bahrain Oil Company refinery was built in 1935, has a capacity of about 250,000 b/d, and was the first in the Gulf. After selling 60% of the refinery to the state-owned Bahrain National Oil Company in 1980, Caltex, a U.S. company, now owns 40%. Saudi Arabia provides most of the crude for refinery operation via pipeline. Bahrain also receives a large portion of the net output and revenues from Saudi Arabia’s Abu Saafa offshore oilfield.

The Bahrain National Gas Company operates a gas liquefaction plant that utilizes gas piped directly from Bahrain’s oilfields. Gas reserves should last about 50 years at present rates of consumption.

The Gulf Petrochemical Industries Company is a joint venture of the petrochemical industries of Kuwait, the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation, and the Government of Bahrain. The plant, completed in 1985, produces ammonia and methanol for export.

Bahrain’s other industries include Aluminum Bahrain, which operates an aluminum smelter–the largest in the world with an annual production of about 525,000 metric tons (mt)–and related factories, such as the Aluminum Extrusion Company and the Gulf Aluminum Rolling Mill. Other plants include the Arab Iron and Steel Company’s iron ore pelletizing plant (4 million tons annually) and a shipbuilding and repair yard.

Bahrain’s development as a major financial center has been the most widely heralded aspect of its diversification effort. International financial institutions operate in Bahrain, both offshore and onshore, without impediments. In 2001, Bahrain’s central bank issued 15 new licenses. More than 100 offshore banking units and representative offices are located in Bahrain, as well as 65 American firms. Bahrain’s international airport is one of busiest in the Gulf, serving 22 carriers. A modern, busy port offers direct and frequent cargo shipping connections to the U.S., Europe, and the Far East.

GDP: purchasing power parity – $10.1 billion (2000 est.)

GDP – real growth rate: 5% (2000 est.)

GDP – per capita: purchasing power parity – $15,900 (2000 est.)

GDP – composition by sector:

agriculture: 1%

industry: 46%

services: 53% (1996 est.)

Inflation rate (consumer prices): 2% (2000 est.)

Labor force: 295,000 (1998 est.)

note: 44% of the population in the 15-64 age group is non-national (July 1998 est.)

Labor force – by occupation: industry, commerce, and service 79%, government 20%, agriculture 1% (1997 est.)

Unemployment rate: 15% (1998 est.)

Budget:

revenues: $1.5 billion

expenditures: $1.9 billion (1998)

Industries: petroleum processing and refining, aluminum smelting, offshore banking, ship repairing; tourism

Industrial production growth rate: 2% (2000 est.)

Electricity – production: 6.185 billion kWh (1999)

Electricity – production by source:

fossil fuel: 100%

hydro: 0%

nuclear: 0%

other: 0% (1999)

Electricity – consumption: 5.752 billion kWh (1999)

Electricity – exports: 0 kWh (1999)

Electricity – imports: 0 kWh (1999)

Agriculture – products: fruit, vegetables; poultry, dairy products; shrimp, fish

Exports: $5.8 billion (f.o.b., 2000)

Exports – commodities: petroleum and petroleum products 61%, aluminum 7%

Exports – partners: India 14%, Saudi Arabia 5%, US 5%, UAE 5%, Japan 4%, South Korea 4% (1999)

Imports: $4.2 billion (f.o.b., 2000)

Imports – commodities: nonoil 59%, crude oil 41%

Imports – partners: France 20%, US 14%, UK 8%, Saudi Arabia 7%, Japan 5% (1999)

Debt – external: $2.7 billion (2000)

Economic aid – recipient: $48.4 million (1995)

Currency: 1 Bahraini dinar (BD) = 1,000 fils

Map of Bahrain